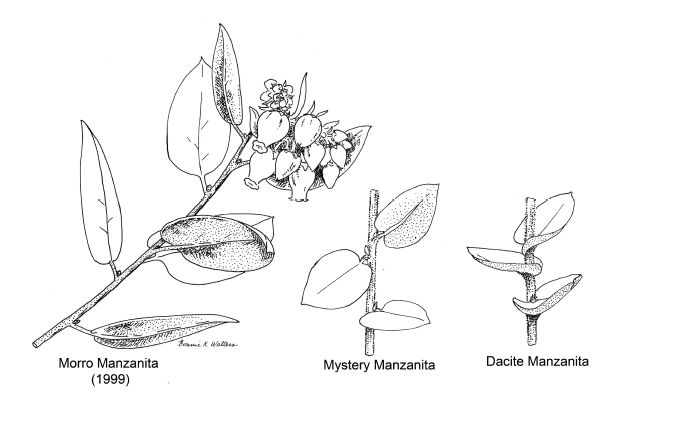

All three of Bonnie’s drawings this time are of manzanitas. One is a repeat of the endemic rare plant commonly known as Morro manzanita or Arctostaphylos morroensis. As you will see, it is included here to serve as a basis of comparison.

The other two drawings are new. One is of a single manzanita plant (maybe a clone) that grows near the mouth of Turri Creek where the Elfin Forest group’s 3rd Saturday Natural History Hike goes when it visits the salt marsh. It is currently in flower. The last is of a species commonly called, dacite manzanita (A. tomentosa ssp. daciticola). It grows nearby in the hills above the mouth of Turri Creek.

There are two other manzanita species that could also complicate the identification of our mystery manzanita. The first and most problematic is Oso manzanita (A. osoensis). Its recorded range is further away from our mystery, but still in the Turri Creek drainage. It is recorded as occurring on higher ridges and plateaus west of Hollister Peak on sandstone or dacite outcrops.

The last possibility is the Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita (A. cruzensis). It is this species that our plant would be if we used Robert F. Hoover’s 1970 edition of The Vascular Plants of San Luis Obispo County, California, for identification because it is the only species (other than A. morroensis) recorded for the area. Dacite manzanita and Oso manzanita were not recognized by Dr. Hoover as valid names.

So which name should we apply to our unknown manzanita? All who have attended these hikes readily concluded that the new manzanita is NOT the Morro manzanita. So if it is not Morro manzanita, what manzanita is it? This question, it turns out, is not easy to answer. This is where the third manzanita drawing comes in. It represents the dacite manzanita (Arctostaphylos tomentosa ssp. daciticola) which is one of two species found growing on the dacite, a granite-like rock which is dominant rock making up the Morro Sister Peaks. Outcrops of this rock weather into thin, infertile soils.

Dacite manzanita is found only within the Turri Creek drainage. I assume most will agree that, if our unknown is not Morro manzanita, it shows a much closer, but not perfect match to the dacite manzanita.

The identification of manzanitas is not easy. First, there are many species (60+ and many subspecies and varieties) recognized as growing in California. Second, I suspect all who have even a passing familiarity with California native plants can identify a manzanita. This means the genus has an easily recognized set of characteristics. It also follows that telling its many species apart is going to be a challenge because species characters must be of necessity minutely different or technical in nature.

However, they can be divided into groups based on the length of their leaf stalks (petioles) and the shape of the leaf blade base. One group, which includes the Morro manzanita, has an easily seen but short (< 4 mm) leaf stalk (petiole) and a smooth, rounded to chordate blade base. A chordate leaf base is going to resemble the top of a valentine heart. The other group has petioles either absent or so short (< 2 mm) that they would not easily be seen unless one looks carefully. Their leaf bases also resemble the top of a valentine heart (chordate). Neither of these traits is present in Bonnie’s Morro manzanita drawing which was probably based on a plant from Montana de Oro State Park. But they are found in the other two drawings.

There are other technical attributes of course, but most of these are not visible without a microscope or hand lens. One character that does not require a microscope, but does require some “digging” is whether or not a manzanita produces a large swelling at the junction where the root turns into the base of the stem. In those that don’t produce the swelling, which includes the Morro manzanita, branching doesn’t usually begin until the main stem (trunk) is a few inches or more, sometimes up to a foot or more, above the ground surface. These are called tree manzanitas due to that single trunk.

Those that branch from the swelling below ground are commonly called shrub manzanitas. Manzanitas that produce this structure tend to form their first branches below ground which produces a bunch of stems in a tight cluster. Again this trait should eliminate the Morro manzanita from consideration because it usually begins to branch at or above the soil surface.

So if it is not Morro manzanita, which of the other manzanitas is it? The Arroyo del la Cruz manzanita, as currently defined, should range from Cambia northward. The Los Oso manzanita is reported to be a relatively tall shrub (3 to 12 feet) and is reported to be restricted to dacite or sandstone outcrops. The dacite manzanita occurs just up slope from our mystery manzanita but is also supposed to be restricted to dacite outcrops. Our mystery manzanita grows on a relatively narrow terrace well above the salt marsh and just below the foundation fill used to raise South Bay Boulevard above the Morro Bay estuary. It is growing in coarse sandy soil probably derived from the fill. It is growing with species characteristic of coastal scrub with a large compliment of weeds. That is, it is growing in a classic, disturbed, man-made habitat. Such habitats are known to allow unusual individuals such as hybrids to occur out of typical range or habitat and become established. In other words, range and habitat can’t be used to limit the possible ID.

So what is its correct identification? I’m still quite unsure. Even the Cal Poly Herbarium is not much help here. I think I could find all three possible species among the specimens within each single species folder in the Cal Poly Herbarium. I do have to admit that the differences among the three short petiolate, chordate leaf-based species depends on the often subtle nature of the kind of hairs (pubescence or trichomes) found on twig and leaf. As stated earlier, these traits require at least a hand lens to observe. I think it is safest to leave it as a mystery manzanita. Maybe, a Cal Poly Senior Project or Masters student will take on this project and find the correct answer for us.

It appears that all the species from the Turri Creek drainage are closely related, at least based on appearance. With additional modern taxonomic techniques maybe it may even be determined that Dr. Hoover was correct back in 1970 when he concluded that all (except Morro manzanita) are the same species.

P.S. After writing the preceding paragraphs, I went back out and observed the three pictured manzanitas again. This time I walked through the Elfin Forest to reacquaint myself with the variability found among Morro manzanita individuals. The plants along the Board Walk are similar to Bonnie’s drawing. But if you observe the manzanitas along the Habitat Trail that goes off the north-east curve and goes toward South Bay Boulevard, you will find that the Morro manzanitas get shorter and shrubbier and their leaves have shorter petioles and more deeply lobed leaf bases. It’s a mini-cline. In other words they begin to resemble more and more our mystery manzanita. So, I’m forced to conclude, at least tentatively, that our unknown manzanita is simply an extreme form of Morro manzanita. If so, it may be the most northern individual of the species. I conclude this in spite of all of us assuring ourselves that is was clearly different from the Morro manzanita we all had pictured in our minds. I still think there is a good student project here, however.