Author: WOODY FREY, Professor emeritus, OH Department, CalPoly, San Luis Obispo. This article was first published in Pacific Horticulture and is reprinted here with permission.

Six miles north of San Luis Obispo, California, up a winding road off Highway 101 at an altitude of about 2,500 feet is what the locals call Cuesta Ridge. Here is found a remarkable grove of trees some 700 acres of Cupressus sargentii. The area, which is known as the Sargent Cypress Forest, was first mentioned in the 1900s by a U.S. Geological Survey team. Charles Sprague Sargent included the tree in the description of Cupressus goveniana in his Silva North America (1896). Willis Lynn Jepson named C. sargentii in honor of Sargent, author of the monumental Silva and first director of the Arnold Arboretum. Image: By Eric in SF

Sargent cypress forests form plant communities found only in California on serpentine soil atop fog-shrouded mountains from Zaca Peak in Santa Barbara County to Red Mountain in Mendocino County. The forest on Cuesta Ridge, in the Santa Lucia Mountains of San Luis Obispo County, is the only undeveloped site that can be easily visited. A paved road was built along the ridge and through the forest as part of a firebreak system in the late 1960s. Sargent cypress trees in this area grow close together and forty to fifty feet in height. Their lower branches fall and the trunks become bare with fibrous, rough, dark reddish or grayish brown to almost black bark. Many trees, especially along the road, have had additional branches removed as part of the early firebreak activities. Looking through the forest of older trees and seeing these pole-like trunks one may imagine that they have been conveniently placed to support a thousand hammocks. Sargent cypress forms a fire-dependent closed cone coniferous plant community. The cones, which remain on the trees for many years, need heat to open and to treat the seeds for germination. Since there has not been a significant fire in the area since the late 1930s, there are few seedlings. Sites of many old fires, however, are evident from the even-aged stands of reseeded trees that give the scene an undulating checker board pattern.

(Obispoensis editor’s note… since this article was published, the Highway 41 fire swept unevenly through the forest and hundred of trees sprouted in the ashes).

Many of the trees appearing to be seedlings are in fact stunted due to poor soil and harsh growing conditions on the exposed ridge. Pygmy forests of stunted trees can be seen in some areas. The soil is derived from serpentine rock formed during the Jurassic Age. Exposed to air and moisture it turns reddish from large deposits of waterborne iron. The soil is alkaline, coarse, gravelly, porous, highly mineralized, low in calcium and high in magnesium. Although thirty to fifty inches of rain fall each year, most is quickly lost through the loose soil. Plants in this area probably depend on moisture from fog to survive. The tree line seems to follow the mean fog line, and the forest starts and stops abruptly because of this. There are some unusual plants in the Sargent cypress forest, many of which show forms and shapes adapted to the serpentine soil darker green and thicker leaves, bushier, more compact habit, and brighter flowers. Many of these plants have considerable ornamental potential.

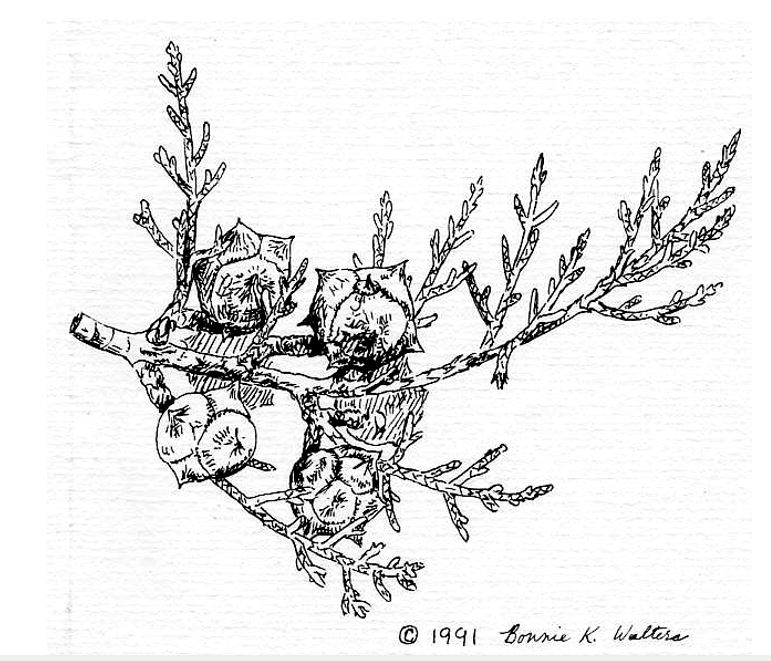

Sketch of Cupressus sargentii by Bonnie Walters

Bulbous plants, found deep in the soil, may last many years. One plant of Chlorogalum pomeridianum var. pomeridianum (soap plant) I have been keeping track of for twenty-five years. Zigadenus fremontii is most common, Friiillaria biflora and F. lanceolata, the chocolate and checkered lilies, are sparse. A special treat in late spring is Calochortus obispoensis, with its hairy, multi-colored petals.

Carex obispoensis covers the damp forest floor in many places, remaining green during the summer from the fog that condenses on overhanging branches and drips to the ground. Sidalcea hickmanii ssp. anomala is a rare spring-blooming herbaceous perennial in the Malvaceae that is endemic in the forest’s northwest edge. (Obispoensis editor’s note… after the Highway 41 fire the Sidalcea became very common for a few years) Chorizanihe breweri, a low and compact herbaceous buckwheat, grows in reddish drifts in open spaces on the rocky soil. A rock fern, Onychium densum (Indian’s dreams or cliff-brake), is common elsewhere, but rare this far south. Unusual strains of Ceanothus cuneatus (buck brush) have flowers of a much brighter blue than those found elsewhere in California. Monardella palmeri, a pennyroyal, is associated with the serpentine soil; on hot days it permeates the air with its pungent minty odor.

A visit to the area is always worthwhile if only to enjoy the outstanding views from the ridge. But spring is perhaps the best time to visit. Everything is fresh and green; most plants are in bloom; and the lichens present a kaleidoscopic display of color and pattern. The chaparral on the outskirts of the forest also is in bloom – Fremontodendron califomicum var. obispoense spills its yellow flowers over the ground; Ceanothus foliosus and

Dendromecon rigida with their blue and yellow flowers stand out against the backdrop of the magnificent Actostaphylos obispoensis, a taller shrub with pink or white flowers.

Although the forest and its surroundings have been touched by mining from the early 1900s to the 1950s and by the firebreak activities of the 1960s, the area has not experienced much development. For this reason, in 1968 the Sargent Cypress Forest and surrounding areas totaling 1,300 acres within the Los Padres National Forest were designated a botanical reserve.

(Obispoensis editor’s note…I thought we have enough about the Carrizo Plain, and as there is a new road into the Cypress grove, it would be a worthwhile excursion for coastal folks. Thanks to Heather and Jim Johnson for finding this great article Older members will recall that our chapter got formed as a result of conservation activism against a giant firebreak that USFS was planning through the heart of the tree grove. Visitors will now see a “doghair forest”, where trees are crowded together, small and in competition with each other for resources. This is typical after wildfire results in simultaneous seed release).

Our family owns property in Sonoma County bordering Austin Creek State Rec Area. Part of the property has a large serpentine outcrop that used to have numerous wonderful specimens of Sargents Cypress. These were ALL apparently killed in the Wallbridge fire earlier this August, 2020 as were numerous others on adjacent properties. We could find no living specimens but the property is very rugged and difficult to walk. There may be survivors. It will be instructive to watch the recovery. Already (November 2020) their cones have opened. Many acres of manzanita dominated chaparral were also cooked, in some places burning all above ground parts but mostly leaving black branches. Almost immediately these shrubs have begun basal sprouting. It’s sad but not unexpected and also necessary.

I recently surveyed a large property in the Walburg fire burn adjacent to Austin Creek State Rec area that had huge Sargent cypress pre-fire. You will be happy to know there are thousands of seedling and sapling trees doing quite well out there. Though 100% of the mature trees were either killed by the fire or removed by PGE as they rebuilt their infrastructure, regeneration is happening despite our drought.

Woody Frey was one of my favorite professors when I was @ CalPoly! Made me think and look at the fine details.