Hoover Award Recipients

The Hoover Award In Recognition of Distinguished Service The Hoover Award was established by the San Luis Obispo chapter in 1974 to recognize a person that has made significant contribution to the success and well being of the SLO chapter of CNPS. The selection is...

On Veldt Grass

Image courtesy of jkirkhart35 | https://www.flickr.com/photos/jkirkhart35/

Some of the most notorious invasive plants such as Carpobrotus, slender leaved ice plant, and cape ivy come from South Africa. Another quite bad one is Veldt grass (Ehrharta calycina). This bunch grass has wide (1/4″) leaves, is glaucous (grey-green) until it matures and turns maroon. From the road it has red tops which turn blond. The seed stems can reach chest height. It is a perennial that produces an incredible amount of seeds and grows throughout the year near the coast, living off fog drip, but mainly follows the rainy winter. Veldt grass is awful because it crowds and overwhelms other plants.

To be rid of it, manually pulling mature plants, including the buried crown of the plant is necessary or resprouting will occur. But this also this often stimulates seed germination. Manual removal must be repeated as seedlings appear from the seedbank. Serious infestations can be sprayed with a grasss-specific herbicide such as Fusilade. Timing is critical, especially after the first several inches of rain. Some applicators report that postemergence treatment to plants over 4 inches tall is much more effective compared to treating smaller plants. If your locale has had Veldt for a long time keep at it until the seed bank is exhausted. The task is very difficult in drought and easy in wet years.

Best wishes weed warriors.

-Mark Skinner

Fire and Fuel Management

Wildfire is a natural part of California ecosystem. However, wildfire also has significant potential for creating conditions that aid in the establishment or spread of invasive plants.

To address these conditions, the California Invasive Plant Council and a team of fire and fuel management experts have developed a set of voluntary best management practices (BMPs) for fire management planning, fuel management, fire suppression, and post-fire activities. The 3rd edition of Best Management Practices for land Managers incorporates these BMPs and is now available.

Download your free copy from www.cal-ipc.org/ip/prevention/landmanagers.php.

Join

Your membership supports these activities and more

- Monitoring rare and endangered plants and habitats

- Acting to save endangered areas through publicity, persuasion, and as an absolute last resort, legal action

- Serving as a science-based resource in public planning processes

- Supporting the establishment of native plant preserves

- Sponsoring workdays to remove invasive plants

- Educational activities including speaker programs, field trips, native plant sales, horticultural workshops, and demonstration gardens

What Do You Get When You Join CNPS?

- The pleasure of contributing to the preservation of Californias incredible native flora

- An exceptional education on Californias native plants through field trips, publications, and plant sales

- The opportunity to learn how to grow native plants

- Artemisia, a quarterly botanic journal

- Flora, a quarterly statewide newsletter

- Chapter newsletter, Obispoensis

Contact CNPS-SLO

CNPS-SLO Board and Committee Chairs Acting PresidentDavid Chipping dchippin@calpoly.edu Field TripsBill Waycott bill.waycott@gmail.com Vice PresidentDena Grossenbacher denagros@gmail.com HistorianDirk R. Walters drwalters@charter.net SecretaryCindy Roessler...

A Few Rare Dune Natural Plant Communities

Everyone’s been to the beach, yes. But how much have we looked around to see what vegetation patterns are there to greet us? San Luis Obispo County dunes, and the Oceano dunes surrounding Oso Flaco Lake in particular, are awesome places that are full of rare plants and at least three rare natural communities, as defined by the Manual of California Vegetation (Sawyer, Keeler-Wolf and Evens, 2009). Let’s explore them. And remember, we give these communities names only to make it easier for ourselves to talk about them. We draw lines around them as we see them repeating in nature, but plants don’t always adhere to our neat little coloring books and boxes. There is really a continuum in vegetation; we separate areas mostly for our own convenience.

Closest to the beach, but not actually on the beach, are what are called dune mats, the Abronia latifolia-Ambrosia chamissonis Herbaceous Alliance and its associations. Some of you may know this as central or southern foredunes (Holland’s Preliminary Descriptions of Terrestrial Natural Communities of California, 1986), others as pioneer dune communities (Holland and Keil’s California Vegetation, 1995). In this community, sand verbena and beach bur-sage are characteristically present. It has a global ranking of G3 and a State ranking of S3, meaning it has less than 21-100 viable occurrences, or occupies a certain rather small area. Dune mats are characteristically found on small hummocks in between sandy areas within about a quarter mile of the surf zone. You might also see sea rocket and the invasive European beachgrass here. Rare plants found here include the surf thistle (Cirsium rhothophilum) and beach spectaclepod (Dithyrea maritima).

Remember that dune communities exist in an unstable environment, with frequent winds, salt spray, and shifting sands. As mentioned above, the communities also shift and sometimes blend into each other. And in extremely protected areas in between the hummocks we often find dune swales containing wetland vegetation. We’ll save those wetland types for another time, but let’s move on to another upland dune community.

Inland from the foredune community and on slightly more stable soils, we find silver dune lupine-mock heather scrub, the Lupinus chamissonis-Ericameria ericoides Shrubland Alliance and its associations. Again, this community has other names such as central dune scrub (Holland 1986, referenced above), and dune scrub communities (Holland and Keil, 1995). Hoover’s Vascular Plants of San Luis Obispo County, 1970 refers to these areas as coastal sand plains. In this community, either silver dune lupine or mock heather is “conspicuous.” This community also has a ranking of G3 S3. This community can extend far inland, to almost 3 miles (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2016). Here you might also see sea cliff buckwheat, California poppy, and occasionally, giant coreopsis (now Leptosyne gigantea), which blends into the next community. If you’re lucky you might find the den of a burrowing owl here, or even see an owl. Rare plant species found here include Blochman’s leafy daisy (Erigeron blochmaniae), dune larkspur (Delphinium parryi ssp. blochmaniae), and Kellogg’s horkelia (Horkelia cuneata ssp.sericea).

South of Oso Flaco Lake is a very rare natural community that many of us have visited and know its location well as Coreopsis Hill. Did you know that the community is called Giant coreopsis scrub? Its official name is Coreopsis gigantea Shrubland Alliance, but as we all know, the major dominant plant species, giant coreopsis, has had its name changed to Leptosyne gigantea. (But note that Leptosyne gigantea is not considered a rare plant.) In our area, this community inhabits the stabilized backdunes, but further south it occurs on bluffs immediately along the edge of the coastline. This community is ranked G3 S3 and is also considered sensitive. According to the Manual of California Vegetation, wherever the giant coreopsis occurs at greater than 30 percent relative cover, we can call the community giant coreopsis scrub. It typically co-occurs with Ericameria ericoides, Artemisia californica, and other dune-lupine-mock heather scrub species. Coreopsis Hill is its northernmost natural occurrence. This is the community shown on our front cover this month. These are only three of our rare natural communities that inhabit dunes along our coastline. Again, it is important to point out that there are variations and subdivisions within these types; these are called Associations. Some associations have been identified and classified; others have not. This means there is more work for our Plant Communities committee to do!

-Melissa Mooney

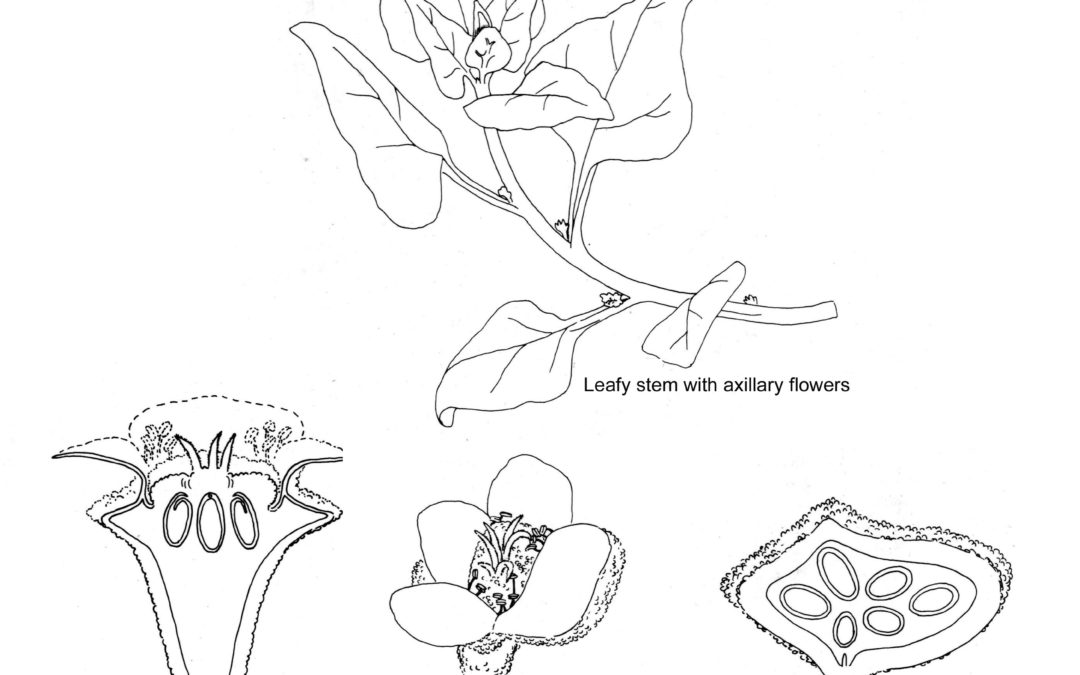

Tetragonia tetragonoides (New Zealand Spinach)

Bonnie’s drawing for this issue of OBISPOENSIS has never been used in any local newsletter. Bonnie drew it for Dr. David Keil and my plant taxonomy text back in the early 1970’s. Why has it not been used? Well, first a look at Bonnie’s drawing will indicate that the species produces inconspicuous flowers. It lacks petals, and the flowers are semi-hidden in the axils of its somewhat succulent leaves, and the species is not native to California. Its common names include New Zealand, or dune, spinach, Tetragonia tetragonoides. For you old timers like me, back in the 1970’s its most common published scientific name was Tetragonia expansa.

New Zealand spinach is considered by many to be an invasive weed. I assume we must go along with that, but my experience with it around here is that it’s not particularly good at it. It prefers slightly salty (halophilic) soils. It also seems to require a bit of disturbance. So, look for it at the upper, less salty edge of salt marsh and/or on coastal benches, especially in disturbed sites where few other species can grow. A few individual plants have been found along the edge of Los Osos Creek, west of Bay View bridge. It is especially common along the trails south of Spooner’s Cove in Montaña de Oro State Park, where it became sufficiently dense to warrant a targeted removal project. It can also be encountered as a weed all along the coast.

New Zealand spinach belongs to a family of flowering plants, Aizoaceae, that is primarily native to the Southern Hemisphere. New Zealand spinach is, in fact native to Southern Africa but has spread to New Zealand and is apparently a serious weed throughout southern Australia. Obviously, it has also been introduced into North America and Eurasia. The genus, Tetragonia, has around a dozen species and its generic name is derived from the four (tetra-) wings that are produced on the green fruit. These wings dry up and essentially disappear in the mature fruit. The inconspicuous flower displays a pale yellow color, but the flowers have no petals, only sepals as it only produces a single whorl of perianth (collective term for sepals and petals). If a perianth has only one whorl, botanists tend to regard them as sepals. These sepals, as well as the stamens are attached to the top of the ovary which makes the ovary inferior. The more famous and probably even more weedy members of the Aizoaceae are the ice plants

(Carpobrotus and Mesembryanthemum).

Wherever New Zealand spinach is found growing, its leaves have been used as a green vegetable. One web source indicated that the Magellan expedition around the world was especially happy to find a patch of it. They would pick the leaves, boil them and then dry (preserve) them for eating. It was particularly good in preventing scurvy! However, note that they boiled the leaves before eating them. The leaves contain enough oxalate chemicals to cause oxalate poisoning. Oxalate chemicals are usually destroyed by boiling.

Dirk Walters

Bluff Trail, Montaña de Oro S.P., site of a New

Zealand spinach removal project to encourage the return of native plants. Photo by David Chipping

Italian Thistle (Carduus pycnocephalus)

Invasive Species Report

A member of the Asteraceae family, Italian thistle is an annual herb native to the Mediterranean region and is widespread in California, Oregon and Washington, however it is not found east of the Sierra Nevada. It was accidentally introduced into United States (Batra et al. 1981) and California (Goeden 1974) in the 1930s. Robbins (1940) reports it as early as 1912 near Fort Bragg in Mendocino County. It forms a deep taproot and prefers fertile, well drained soils but is found in disturbed areas, roadsides, pastures, meadows and grasslands. It dominates sites and crowds out native species and discourages wildlife from entering infested areas. It grows well in oak savanna and can carry grass fires to tree canopies. Although Italian thistle can grow to over six feet it is usually knee high and is often present in clusters. Its leaves are white-woolly below, hairless-green above and deeply cut into two to five pairs of spiny lobes. Stems are slightly winged. The thimble-sized flower heads in pastel shades of rose, pink to purple flowers are clustered in groups of two to five are covered with densely matted, cobwebby hairs. Italian thistle is bisexual and a single plant can produce 20,000 seeds in one season (Wheatley and Collett 1981). Its light seeds are spread by lodging (bent or broken stems in contact with the ground), wind, vehicles, and animals and also may spread from seed-contaminated hay and soil from infested quarries. To remove Italian thistle dig them out 2-4 inches below the soil before flowering. Mowing is a waste of time, in fact, plants cut 4 days after flowering can still produce viable seed. Italian thistle seedbank may last up to 10 years. Intensive grazing by sheep and goats is effective. A pre-emergent and growth regulator such as Milestone is one of the most effective herbicides for thistles and generally does not harm grass. Did I say don’t touch Italian thistle? Wow does it hurt! Use your thickest gloves!

A member of the Asteraceae family, Italian thistle is an annual herb native to the Mediterranean region and is widespread in California, Oregon and Washington, however it is not found east of the Sierra Nevada. It was accidentally introduced into United States (Batra et al. 1981) and California (Goeden 1974) in the 1930s. Robbins (1940) reports it as early as 1912 near Fort Bragg in Mendocino County. It forms a deep taproot and prefers fertile, well drained soils but is found in disturbed areas, roadsides, pastures, meadows and grasslands. It dominates sites and crowds out native species and discourages wildlife from entering infested areas. It grows well in oak savanna and can carry grass fires to tree canopies. Although Italian thistle can grow to over six feet it is usually knee high and is often present in clusters. Its leaves are white-woolly below, hairless-green above and deeply cut into two to five pairs of spiny lobes. Stems are slightly winged. The thimble-sized flower heads in pastel shades of rose, pink to purple flowers are clustered in groups of two to five are covered with densely matted, cobwebby hairs. Italian thistle is bisexual and a single plant can produce 20,000 seeds in one season (Wheatley and Collett 1981). Its light seeds are spread by lodging (bent or broken stems in contact with the ground), wind, vehicles, and animals and also may spread from seed-contaminated hay and soil from infested quarries. To remove Italian thistle dig them out 2-4 inches below the soil before flowering. Mowing is a waste of time, in fact, plants cut 4 days after flowering can still produce viable seed. Italian thistle seedbank may last up to 10 years. Intensive grazing by sheep and goats is effective. A pre-emergent and growth regulator such as Milestone is one of the most effective herbicides for thistles and generally does not harm grass. Did I say don’t touch Italian thistle? Wow does it hurt! Use your thickest gloves!

-Mark Skinner: Invasive Species Chair

What I’ve Learned: I need patience and I don’t have the right shoes

Image: By Gmihail at Serbian Wikipedia (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 rs (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/rs/deed.en) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

I volunteer at the botanic garden Tuesday mornings. The display of yellow Viola on the undeveloped portion of the hills was wonderful this year and it occurred to me that there would be lots of seeds. I would really like to have the propagation crew at the garden try to grow some of these as I think they would make a nice addition to our gardens. Granted they disappear in the heat of the summer but they could make a nice groundcover under some of our shrubs and need no water in the dry time. So I approached Eve. Eve is the person who started the garden as an extension of her senior project at Cal Poly. She was receptive to the idea. I asked if I could take a bit more for other uses. Again the answer was yes and extended to some of the other plants on the hills. So when I thought the seeds might be ready I ventured out.

These are hills that are brown in the summer. They are covered with oats and ripgut and some other not so nice plants. But there are patches of Viola and Sidalcea and Sisyrhincium. So I had a goal of collecting all three. Finding those patches was not always easy. The plants disappear into the dried grasses. But I could find some. And in my wandering looking for patches I was excited to discover that not only are there the invasive sorts of grasses but there was lots of Stipa pulcra, some Melica californica, Melica imperfecta (or at least a different kind of Melica), Elymus triticoides (I think), Elymus condensatus, Hordeum bracyantherum and the most exciting find, for me, was some Danthonia californica. I am not collecting seeds of those grasses because they are not represented in great numbers and I want all the seed that’s there to possibly increase populations. But I am collecting the seeds of the Viola, Sidalcea, and hopefully the Sisyrhincum.

However, patience is a requirement. Finding the patches of Viola was not nearly as challenging as finding the seeds ready to gather. I am honing my observational skills and getting up close and personal with the plants. I was looking for black, ripe seeds so black drew my attention. Often the black was a little beetle that I saw only on violets. Is this a good bug or a bad bug? I have no idea. But if it is providing food for the birds in my book it’s a good bug. Perhaps it’s one of those specialist bugs that only use one plant. Questions. Down on my knees I can see the developing seed capsules and I have observed that as they ripen they lift and point to the sky. Once ripe, the capsules pop open. Sometimes a few seeds remain in the opened capsule. Whether these are defective or not I don’t know but I have collected them. At least they are black. Picking a few capsules early results in green seeds. I have picked a few, unopened but upturned, which have resulted in the sound of popping seeds in the paper bags at home. I have gotten some black seeds out of these. My favorite find is to see the open capsule, still green, and filled with black seeds. Treasure! But it has taken weeks of venturing up on the hill to get a few tablespoons of seeds. Some of these will find their way to the seed exchange.

The Sidalcea is another story. I found that many of the flowers did not develop into seeds, but in some areas there were more that developed than others. Does this reflect the presence of more pollinators in some areas than others? In some areas the stalks were half gone. Are they browse for deer? More observations lead to more questions. But I did collect a few seeds that seemed to be ripe. The capsules on these plants seemed to dry with the seeds remaining in the capsule. But as they dried they would separate a bit and I found that if I just brushed my fingers across a capsule seeds would fall into my hand. I found capsules with just a few seeds remaining so assumed these were ripe. I don’t have many seeds of these but after sharing with the botanic garden a few will end up at the seed exchange. You should want these. I have a Sidalcea grown from seed that has been blooming for several months in my garden. I think it’s beautiful.

As for the Sisyrhincium, I don’t have seeds yet and am not sure that I will. Those patches, which were so obvious and seemed so huge when they were covered with their blue-purple blossoms, are very hard to find when there is no flower to beckon. Those that I have found are not yet ripe. The capsules are still green and I don’t know if I will have any luck finding ripe seeds. But I am going to try.

What about not having the right shoes? The shoes I wear at the botanic garden are really old worn out hiking shoes with that open mesh sort of fabric for breathability. They are really great grass seed collectors. Those seeds penetrate through the open mesh and through my smart wool socks and into my skin. Almost intolerable. Before I drive home I have to remove my shoes and get rid of those seeds. I am pleased to find that they collect Stipa seeds too which means that there are plenty of Stipa seeds to be had. But I am very conscious of the fact that I don’t want to be transferring these seeds to the trails so they are no longer used for hiking.

Reminder: Seed exchange before the October meeting.

-Marti Rutherford