Introduction

October and November are when our Chapter gets serious about growing native plants. We have a November meeting devoted to it as well as our annual plant sale. This got me to remembering some articles written and drawings drawn by Alice G. Meyer that are in the Historians files. The mechanical typewriter written and her hand drawn copies on are on 8½ x 14 paper. I don’t think they were published in our chapter newsletter as I don’t remember us ever using that format. I think Alice may have produced them back in the 1970s or 1980s for the Morro Coast Audubon Society. If so, I hope they will forgive us for reprinting them. They’re too good to lie forgotten in a file somewhere.

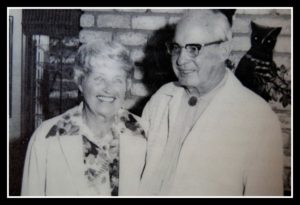

Alice, along with her husband, Henry (Bud), were our Chapters first members to be elected Fellows of the State CNPS. Alice was extremely interested in native plant gardening and had a fantastic native plant garden in her Los Osos back yard.

It was Alice who suggested in the Early 1970’s that our Chapter have a Native Plant Sale! She then went ahead and planned it. The first one was small and contained only plants grown by Chapter members as well as a few plants propagated by Cal Poly Students in a Native Plants Class several years before and that were scheduled to be thrown out. It was quite successful! The Chapter has had a plant sale the first Saturday in November ever since.

Alice ran the sale until 1990 when the current plant Sale Chair, John Nowak, took over. Note, we have had ONLY two plant sale chairs since the early 1970s. This points out one of the strengths in our Chapter. Our member often have a long term commitment to the tasks required for running a CNPS Chapter.

Enough history, let’s let Alice tell us about a fantastic native garden plant in her own words.

Dr. Dirk Walters

PLANT OF THE MONTH

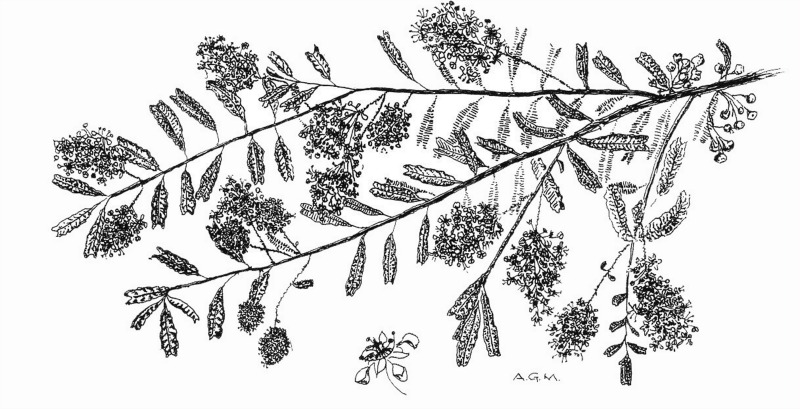

Ceonothus hearstiorum

by Alice G. Meyer

The Hearst mountain lilac grows on low hills near the coast, just north and south of Arroyo de la Cruz on the Hearst Ranch. It is not known to grow anywhere else, and, is a rare and endangered plant. It is a spreading prostrate shrub, known botanically as Ceanothus hearstiorum (See-an-OH-thus hearst-ee-OH rum). Horticulturally, it is an ideal ground cover, 4 to 8 inches tall, handsome all year , but especially when it flowers in March and April. The shrub is not widely available, but some growers do propagate it.

Hearst mountain lilac grows best on the coast, in full sun. Inland, it prefers filtered sunlight, and should have some supplemental water during the hot months. Once established, it will survive on the coast with normal rainfall, but will tolerate some summer water. In dry years it needs extra moisture to maintain it best appearance. An observant gardener will note stress and take necessary action. Inland supplemental water during the hot months is a must.

Wherever it is grown, good drainage is important, and there should be no basin around the shrub as water standing around the trunk will cause bacterial problems. When planting, it is better to plant it on a slight mound, so that water runs outward towards the drip line, but the soil should not be piled up around it higher than it was in the container.

Photo by Stan Shebs

- The edges of the dark green leaves are curled downward between the veins, making them seem notched and giving the leaves a crinkled appearance.

- The deep wedge-wood blue flowers are in tight, upward facing racemes ½ to 1½ inches long.

- Each flower is no more than 1/8 inch across.

- If you remove one flower and inspect it with a magnifying glass you will find that it has a stem (pedicel) of the same color as the flower, and the five pointed sepals fold inward to the center around the three-parted stigma.

- The spaces between the petals are like five rays extending from the center to the edge of the flower.

- Near the outer edge of each ‘ray’ a yellow stamen rises, and at the very edge another petal extends outward. This petal is thread-like at the base, and at its outer edge it widens out to a spoon-like shape with a bowl about 1/16 inch long.

Because the flowers are so small, a great many are crowded into each raceme. The groups are beautiful, but close inspection of an individual blossom reveals its complex structure.

Should you grow this shrub, it is advisable not to let too many layers of branches build up on top of the shrub, as it will tend to die out underneath. Keep the shrub very prostrate. Where the plant is native, it is browsed by deer and cattle, and this tendency is thus resolved.